EU Election Preview: The Pendulum Swings Back?

The Greens' big wins in 2019 heralded the Green Deal under the von der Leyen Commission; five years on, polls show a sharp swing in popular support to the right. A new Citi Research report previews the elections, explaining why the Green Deal may wind up being watered down even though Ursula von der Leyen looks set to stay on as EU Commission president.

The following is a freely accessible summary of a published Citi Research report.

In a new report from a team led by European economist Christian Schulz, we preview the upcoming EU elections, which will elect 720 Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) to five-year terms from national lists weighted by population according to proportional representation. Polls suggest a swing to the right, away from the Greens and Liberals, and while EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen looks set to stay on, the Green Deal may wind up being watered down, with a new focus on defense, immigration and reducing the EU’s footprint in European policymaking.

The EU operates like most Western parliamentary democracies, with a parliament effectively made up of two houses. The European Council forms the lower house, and can be thought of as the “Chamber of States,” as each Member State has one seat (though not necessarily with equal voting rights) and is represented by its national leader or government. The upper house is the European Parliament, which can be understood as the “Chamber of People,” since its members are directly elected. Power is unambiguously skewed toward the lower house, both in terms of law-making powers and all matters in which EU monies are involved, and the composition of the EU Commission — the executive body of the EU — is derived from the Council, not the Parliament. As a result, the impact of the European elections is more indirect than direct. The elections offer a reflection of public opinion, not just across Europe but also within individual countries, and this can increase or decrease the political capital in the hands of the Council’s members.

Hundreds of political parties will be in the running for the 720 seats, with 212 having made the cut in 2019’s vote. These national parties will then align with like-minded parties from other member states to form parliamentary groups. That’s a much looser arrangement than groups found in national parliaments, but the groups have established some common views and priorities for the next five years, and some have nominated lead candidates, known as Spitzenkandidaten, for the post of EU Commission president.

Here's our quick overview of the major groups: The Left’s goals include better employment and social rights, a fair wealth distribution, stronger environmental protections and equal pay. The Greens/EFA reject fiscal austerity and reformed fiscal rules, and demand post-2030 climate targets and a “human” migration pact. The Social Democrats’ priorities include more EU-wide regulation of the housing markets, strengthening women’s rights, greater environmental spending and more EU-wide social and labor rights. Renew Europe favors using EU funds to promote the rule of law and enforce human rights while supporting the Green Deal. The European Peoples Party (EPP) is focused on more investment in Europe’s defense industry, tougher immigration controls, deregulation, and a more “realistic” approach to climate neutrality in 2050; its Spritzenkandidat is von der Leyen, the current Commission president. The European Conservatives and Reformers (ECR) want “less Europe” in order to strengthen member states and to reduce the “cost of Europe,” such as by shrinking its institutions or stopping climate-change policies. Identity and Democracy is focused on being tough on immigration, opposes EU membership for Turkey and advocates stronger national parliaments and national referendums.

Polls show shift to right

In 2019, big wins by the Greens heralded a focus on the Green Deal, a set of European Commission policy initiatives aimed at achieving EU climate neutrality by 2050. Five years later, we see the pendulum as swinging back. Von der Leyen’s EPP seems clearly in first place according to polls, followed by the Social Democrats, with a wide-open competition for third place. The Greens seem likely to be the big losers from the elections. As a caveat, groups’ composition can change, impacting the final ranking.

At least at the start of the legislature, the groups’ main aim will be to influence the distribution of posts across European institutions; one of the parliament’s key powers is its right to approve and dismiss the EU Commission. The Council proposes the candidates, with Parliament’s groups trying to influence the choice of president by naming Spitzenkandidaten and agreeing to approve the Commission on the condition that the Council accepts the winning party’s candidate as president.

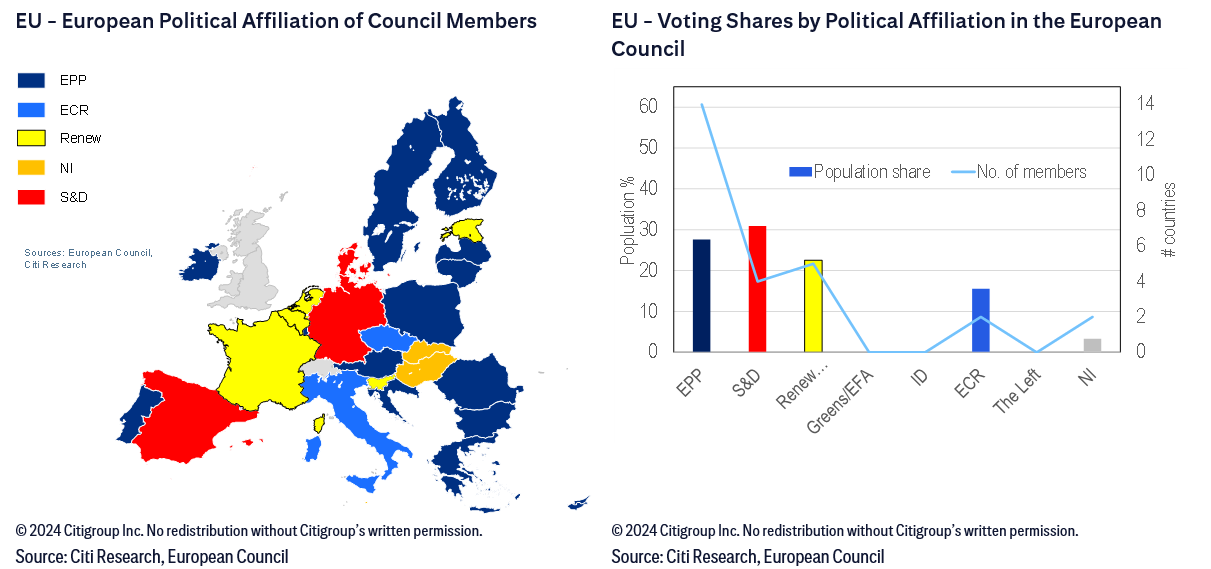

We think von der Leyen should be in a strong position to be re-elected if the EPP remains the largest party in parliament, as polls predict. When our note was written, 14 of the 27 EU member states were represented by EPP politicians, though the EPP leaders only represent 27.6% of the EU population, and none of the “Big Four” of Germany, France, Italy and Spain. To gain the necessary 65% majority, von de Leyen will need support from the Social Democrats (who represent 31% of the population) as well as from Renew Europe (22.6%). Other key positions will include the presidents of the European Council and the European Parliament.

Impacts on EU and national politics

Individual leaders’ political capital stems in part from whether the policies they advocate win or lose votes in domestic elections. So, for instance, French President Macron may have more difficulty gathering support across the continent for more concentration of federal power if the Renew group sees large losses across Europe and more particularly in France, while Italian Prime Minister Meloni may have more leverage if the ECR sees strong vote gains. We see Meloni as a person to watch given these elections: Von der Leyen has already made clear that she will cooperate with her, and if Meloni’s Fratelli d’Italia party moves from the ECR to the EPP, she could have significant sway over EU positions.

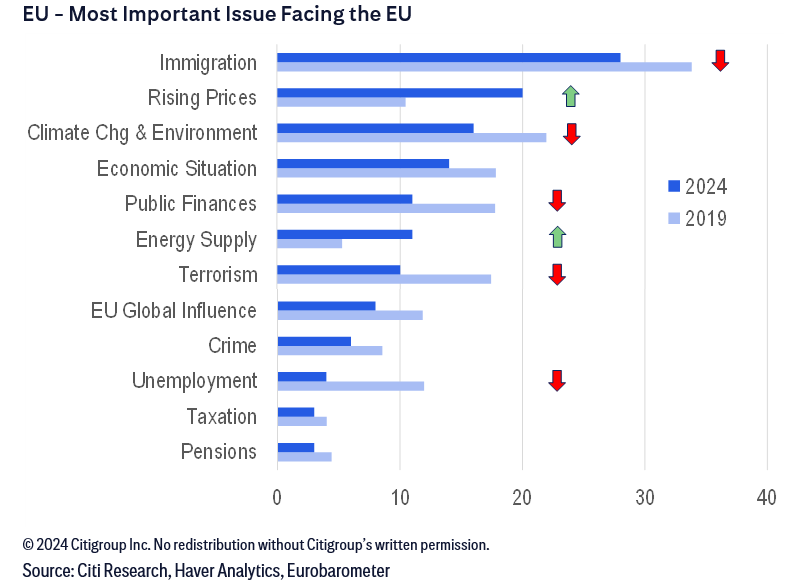

What’s on EU voters’ minds? Immigration remains the most pressing issue, but its importance has waned since peaking in 2015. Climate change and its environmental impacts have also begun to fade as a perceived EU priority, in favor of high inflation. Energy surged to become a top priority in 2022, but has since dropped back in voters’ minds. Meanwhile, a recent poll shows more than 75% of European voters favor a common defense and security policy at the EU level and think the EU should reinforce its military capacity. And EU voters’ trust in the EU has significantly improved since the pandemic.

Upcoming debates for the next term could include the prospect of enlarging the EU and reform of its current voting processes; the 2028-2034 fiscal framework; completion of a banking and capital-markets union; greater defense integration; free trade and supply-chain issues; the push and pull between the Green Deal and cheap energy; and asylum policies.

Existing Citi Research clients can follow this link to access the full report, which also includes a nation-by-nation look at implications of the elections and a discussion of potential impacts on equities.