China’s Faltering Reopening: Ripple Effects in the EU and Beyond

China’s economic reopening has stalled, and Citi Research economists have downgraded their 2023 GDP forecasts for the country to below 5%. But slowing activity data have also triggered new measures from Beijing, with more likely to come.

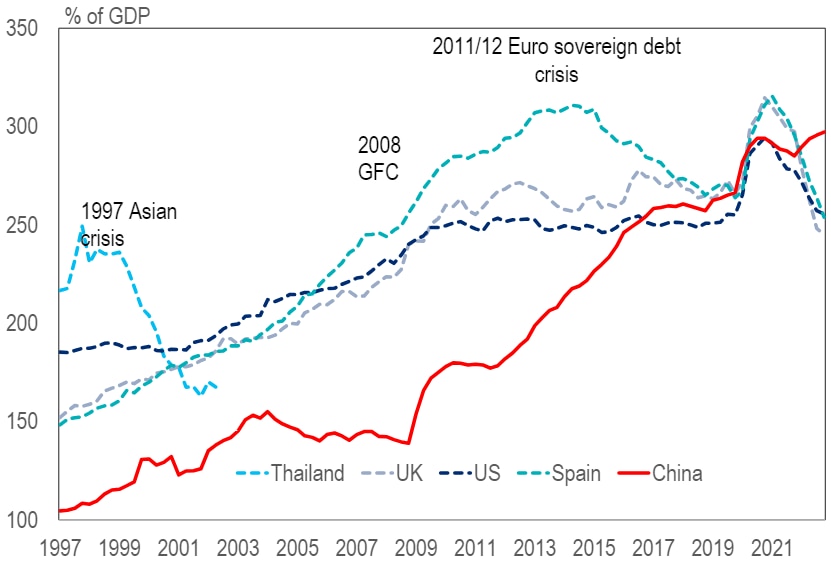

Selected Economies - Total public and private debt (% of GDP)

© 2023 Citigroup Inc. No redistribution without Citigroup’s written permission.

Source: Citi Research, BIS

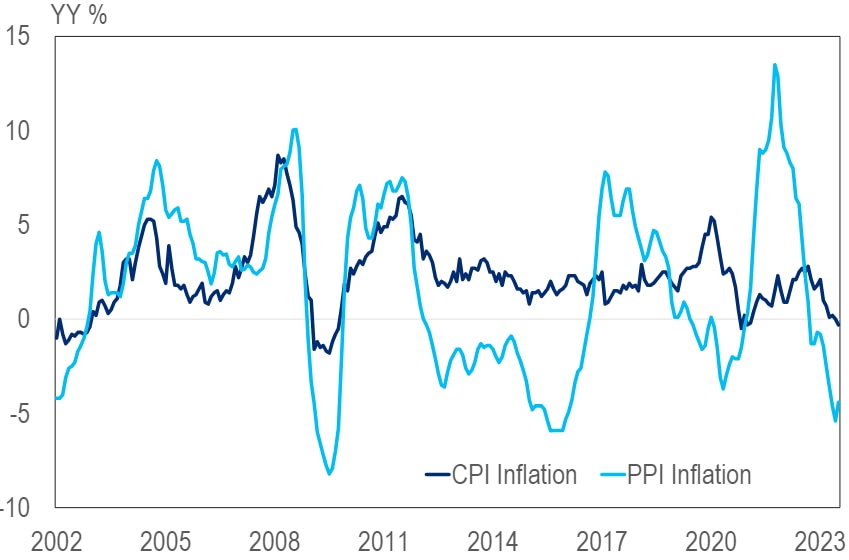

China - Consumer and Producer Prices (YY %)

© 2023 Citigroup Inc. No redistribution without Citigroup’s written permission.

Source: Citi Research, BIS

Currently, economic risks in China remain skewed to the downside, the Citi Research report said. A further slowdown in China growth would negatively impact Europe via reduced exports to China and less investment in new capacity at home, it added. On the positive side, European consumers may benefit from more choice and lower prices if Chinese exporters try to replace flagging domestic demand with more exports. The composition of China’s recovery may also be changing, with new policy support measures targeting infrastructure/property, the report noted.

China’s economy is grossly undershooting expectations since the end of zero-Covid policies. At peak optimism in April, Citi Research analysts expected the Chinese economy to expand by 6.1% this year; now that forecast has dropped to 4.7%.

While Chinese authorities are reacting to the growth weakness, aggressive stimulus as in 2016, for example, seems increasingly unlikely as worries about side effects abound: BIS data show that China’s total debt has increased to nearly 300% of GDP.

To some policy makers, that suggests belt-tightening and accepting lower trend growth may be the price of avoiding a financial crisis. The scope for rate cuts is limited by simultaneously high interest rates in advanced economies and thus the risk of de-stabilising capital outflows.

However, others argue that Chinese authorities are falling behind the curve as real rates have risen by 300bp since the middle of last year despite recent modest rate cuts as the economy has fallen into deflation. The risk of Japanification is high. Either way, China is heading for lower domestic demand growth than in the past, the authors say.

China’s economy is the second-largest national economy, accounting for 18% of global GDP, 2pp more than the EU. Its shares in global exports (2022 14.6%) and global imports (2022 11.0%) are only slightly smaller. What is more, these shares have risen from less than 5% of global GDP and just over 5% of global exports and imports in 2003. An end of China’s growth story will likely have repercussions that go beyond short-term trade fluctuations.

Emerging markets are likely to be hit most. Many Asian economies are interwoven with Chinese supply chains, while economies as far away as Africa and Latin America are exposed via commodity exports. In addition, China is often a large investor in infrastructure in these markets.

Among industrialised economies, the geographical proximity points to Japan and Australia as most exposed to a China slowdown.

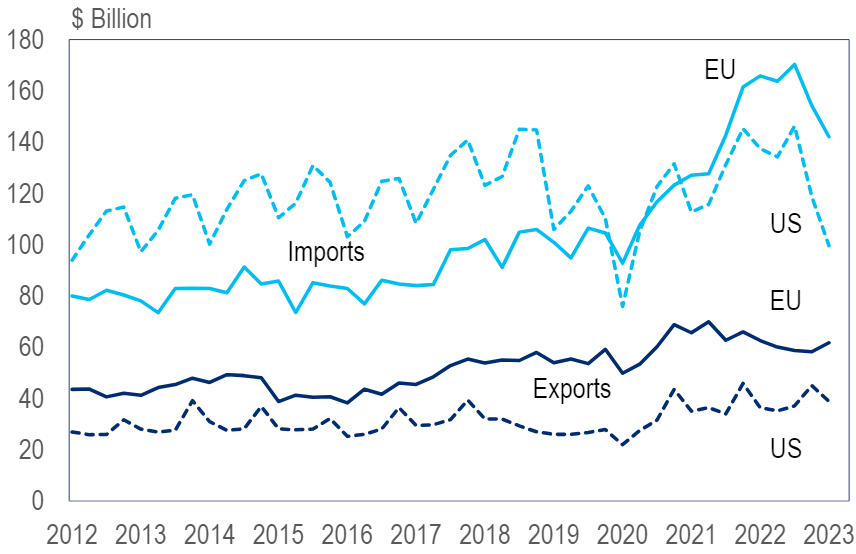

US, Euro Area - Exports and Imports to China

© 2023 Citigroup Inc. No redistribution without Citigroup’s written permission.

Source: Citi Research, NPB

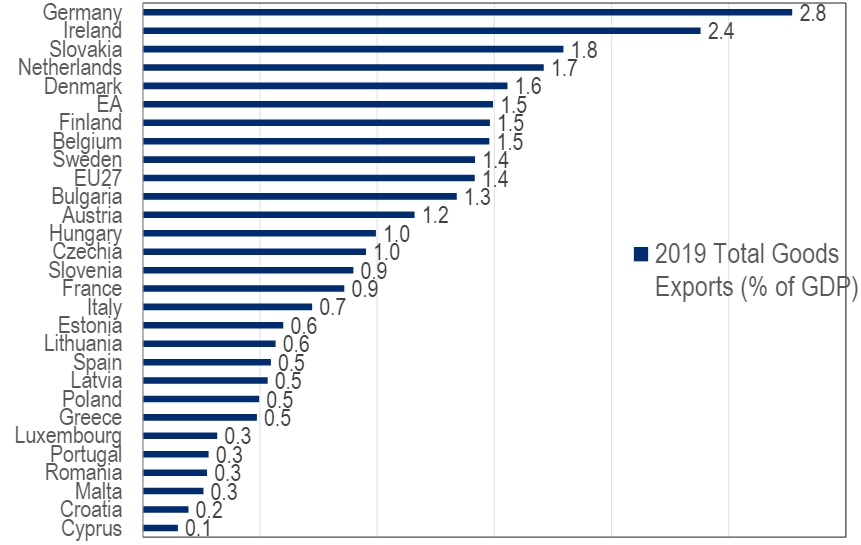

EU - Exports to China (% of GDP)

© 2023 Citigroup Inc. No redistribution without Citigroup’s written permission.

Source: Citi Research, NPB

However, of key importance is also the diverging exposure between the US and Europe. Whereas the US and the EU imported roughly the same amount from China over the past five years, European exports were two-thirds larger than US exports to China and have also been growing faster. Within Europe, Germany is by far the most exposed, with exports to China accounting for 3% of GDP, compared to less than 1% of GDP in France or Italy (see the charts above).

Political impact

China’s economic slowdown could also have political implications. The “Chinese dream” of leaving poverty in rural areas behind to join the urban middle classes could diminish political stability internally in China. That could also raise tensions with neighbouring countries, as well as with the US and Europe.

Since the US-China trade disputes broke out in 2016-2020 – aggravated by the experience of the pandemic and Russia’s attack on Ukraine – western economies aim to make their supply chains more reliable, including by removing politically risky locations from their supply chains. This could mean wholesale re-onshoring, but also, large firms diversifying their supplier base and smaller firms increasing warehousing along the supply chain. Weaker Chinese growth lowers the attractiveness of producing in China and may therefore accelerate the process to the benefit of production in other Asian economies or Europe.

However, while it may be feasible to make the US and European economies more independent of Chinese supply, substituting Chinese demand will be much more difficult especially for Europe. For example, China’s car market is as big as the US’s and Europe’s combined, and for electrical vehicles, China’s market is double that of the US and Europe combined, according to data from Germany’s carmaker federation VDA. In some markets, China is at the cutting edge of technology and not selling there would amount to losing the know-how not just to succeed in China but in the whole world. The analysts say they would therefore expect Europe’s approach of “de-risking” to prevail over “de-coupling” for the coming years.

For more information on this subject, and if you are a Velocity subscriber, please see: Multi-Asset - Evolving China Macro: Impact on the European Economy and Equities (originally published on 1 September 2023).

Citi Global Insights (CGI) is Citi’s premier non-independent thought leadership curation. It is not investment research; however, it may contain thematic content previously expressed in an Independent Research report. For the full CGI disclosure, click here.