The UK Election: Robust Majority, Sufficient Authority, High Stakes

The UK elections brought an emphatic victory for Labour, with the scale of the swing amongst the largest in electoral history. That suggests a more forward-looking fiscal approach, one whose implications we consider in a new Citi Research note.

The following is a freely accessible summary of a published Citi Research report.

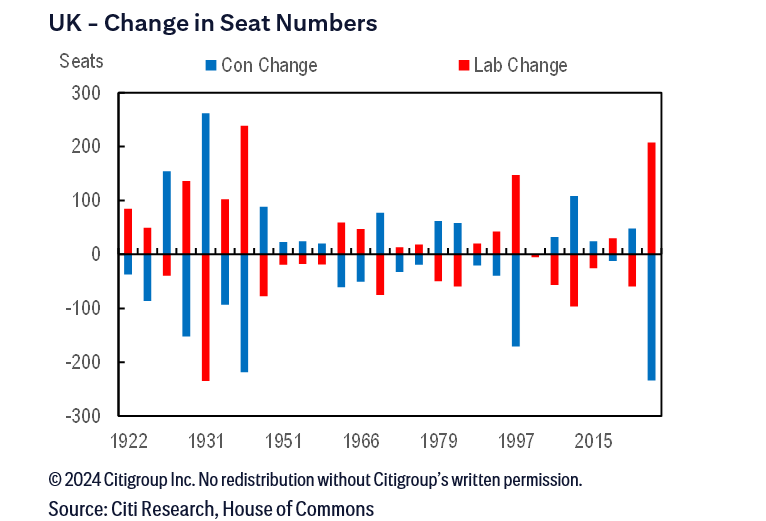

In a new Citi Research report, Benjamin Nabarro and team look at the historic landslide victory for the UK’s Labour Party. The 174-seat majority (our report used exit polling’s prediction of 170 at the time of publication) is marginally less than 1997, but a larger overall swing in the number of seats; Labour has recovered from their weakest postwar performance to come close to their strongest. Besides Conservatives’ losses, the other significant stories were a large boost for the Liberal Democrats, a loss for the Scottish National Party (SNP), and an unexpectedly strong performance for Reform. By way of historic perspective, the Labour seat gain is the highest since 1945 and the Conservative seat count is now below the party’s previous 1906 nadir, with the lowest share since 1832.

Looking at the initial results, we noted two clear shifts. The first is the substantial swing towards Labour away from the Conservatives in a conventional sense. The second is that Labour’s strength was boosted by the rise of the right-wing populist Reform party and the split of the right-wing vote. Of seats that voted Conservative in 2019, the exit poll showed an 18-percentage-point (pp) rise in support for Reform and a 28pp drop for the Conservatives. The UK’s first-past-the-post electoral system then compounded Conservative losses.

That means that while the result may be robust, the direct endorsement of Labour’s agenda may be somewhat less emphatic than headline numbers would suggest, a factor also compounded by turnout that initial numbers suggested had fallen. The challenge now for Labour is solidifying underlying support to match the scale of the swing in seats.

For fiscal policy, the results did little to change our expectations. We had expected a robust 120–150 seat majority; a marginally stronger outcome further boosts the authority of Labour’s leadership. Now that it’s secured a robust majority, we think Labour should plan for a full five-year parliament. Given its difficult fiscal inheritance, utilizing the associated flexibility will be central to its re-election prospects. This suggests a relatively tight fiscal approach upfront, which would create policy space for later in the parliament and also accelerate disinflationary processes that should, in turn, enable rates to fall.

Therefore, we think existing fiscal tightening will continue as planned into the 2025 and 2026 fiscal years. We also see further revenue increases as likely come Labour’s first fiscal event. This will likely weigh on growth at first, before rates driven lower and more public spending enable a robust improvement in the economic trajectory from 2026 onwards.

After a flurry of initial legislation and a delayed summer recess, we see fiscal announcements likely in October at the earliest, after the party conference. We expect a tight one-year interim spending settlement ahead of an autumn budget, before a dialing up of spending later in the parliament as more fiscal space becomes available. In part here, we continue to think Asset Purchase Facility reform is likely over the course of the parliament. But that’s a rather complicated shift that we don’t expect to come until fiscal 2025 or 2026, or even afterwards.

Reform saw its leader Nigel Farage win in Clacton, giving the party a prominent Westminster presence. And the party clearly took a substantial share of the popular vote, especially in Conservative-supporting areas. For the Conservative Party, the question now is whether to do some kind of deal or go it alone. Conservatives such as former Home Secretary Suella Braverman and figures such as Jacob Rees-Mogg have argued for bringing Farage into the party, while the likes of Kemi Badenoch and former PM Boris Johnson have argued against it.

Regarding the EU agenda, an implication of the split in the right-of-center vote is that Reform is now the second-placed party in many Labour seats, especially in regions such as the North East. We continue to think Labour will make progress on its supply agenda, including the adoption of a more proactive industrial strategy. An easing of trade frictions with the EU will likely be part of the story around growth, but we think Labour will progress only with caution. We think free(er) movement — which would probably be required to achieve more sweeping improvements in the trading relationship — remains unlikely in this parliament.

We see the SNP’s poor performance pointing to waning risks around independence. An SNP government in Holyrood will still likely push the case, but with weaker representation in Westminster we expect it will be difficult to make discernable progress. Overall, we think the risks of a second independence referendum have fallen notably, at least for the near- to medium-term.

The results boost our conviction that the UK has the necessary near-term clout to navigate legacy challenges associated with the pandemic’s fiscal and social overhang. We also think the scale of Labour’s majority adds to the momentum behind supply-side reform. Both are reasons for economic optimism in the medium term.

But the rise of Reform (and, to a lesser extent, the Greens) also speaks to a deeper economic frustration after years of weak real income growth. We think it’s now more likely that elements of a more fiscally unorthodox approach are incorporated by the opposition, either as Farage enters the Conservative Party or as the existing Tory leadership adopt elements of Reform’s platform to squeeze Reform politically. Either way, this suggests that fiscal risks associated with, for example, the agenda of former Prime Ministership of Liz Truss are still with us. Material improvements will likely be necessary if Labour is to push back increasingly prominent populist fiscal voices, and the stakes remain strikingly high.

We also note that as in 2019, shifting interactions between parties have once again compounded somewhat more modest shifts in fundamental opinion. That means the current outcome probably overstates structural political stability. In the near term, that shouldn’t detract from what we think is a broadly constructive economic development. But just as voters lent their votes to the Conservatives in 2019, so too some seem to have opted for Labour in 2024, perhaps more out of frustration than proactive support.

Regarding rates, Labour’s victory came with almost no uncertainty premium priced into the market. The election does end the blackout for the Monetary Policy Committee. Since June’s meeting, the market has been pricing around a 54% to 58% chance of an August cut and will be hoping for clues as policymakers await key data in mid-July.

Existing Citi Research clients can follow this link to access the full report.