A recent report from Citi Research’s Johanna Chua looks at how tensions between the U.S. and China could result in broader fragmentation.

The report takes a closer look at four contributing factors and how this potential shift could play out.

1: Friendshoring is slow and costly

The initial response to heightened geopolitical risks is more often a reshuffling of trade flows and sourcing, rather than significant investments in new capacity, the report says.

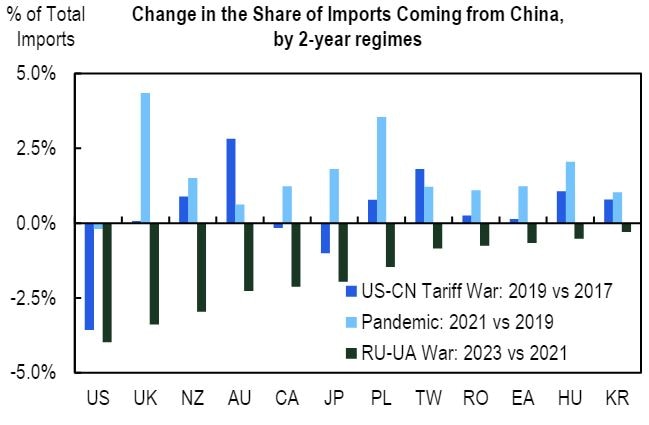

They point out that little evidence exists of material friendshoring--concentrating on trade with geopolitical allies-- in the aftermath of the 2018–2019 U.S.–China tariff war, and even less during the pandemic. It wasn’t until the aftermath of Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine and the need to reduce import dependence on China that the concept of friendshoring began to take hold.

Reliance on Chinese imports fell for many "Western" allies only after the Russia-Ukraine war

© 2024 Citigroup Inc. No redistribution without Citigroup’s written permission.

Source: Haver, Citi Research

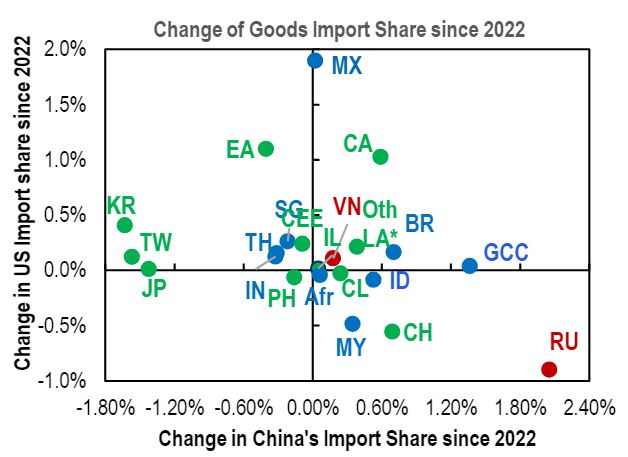

Change in US import share vs Change in China Import share, 2023 vs 2021

© 2024 Citigroup Inc. No redistribution without Citigroup’s written permission.

Source: Haver, Citi Research. Note: We color countries according to their alignment in the UN vote to suspend Russia from UNHRC: green for supporting it, blue for abstention and red for voting against.

Friendshoring’s reconfiguration of supply-chain capacity depends on both policies and macroeconomics, and the authors expect the push for this tactic to intensify in coming years. While there has been an uptick in announcements of supply-chain relocation to India and Mexico in recent years, actual foreign direct investment (FDI) flows generally haven’t registered a notable increase. That said, the authors add, there’s a caveat: High interest rates could have acted as a drag on FDI, a situation that could change as more central banks begin cutting rates.

On the other hand, China’s policies are increasing the economic costs of de-risking, and this could slow any friendshoring trend. Ultimately, the authors note, friendshoring of supply chains looks far easier for the U.S. than China.

China lacks high-tech “friends” that could fill the void if there’s a reduced reliability of sourcing high-tech products from the Western bloc.

2: Industrial policies on both sides

China will keep doubling down on industrial policies, the authors say, and Western bloc countries will also increase their own implementation — for example the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act and Chips and Science Act of 2022.

While such policies can spur innovation, many of them have protectionist elements too. The note points to semiconductors as a case in point, with the U.S. tightening China’s access to critical chip technologies and China reportedly asking top telecom carriers to phase out foreign processors in their networks.

The U.S. is pursuing an aggressive reshoring strategy for chip production, aided by significant subsidies-- and since South Korea, Taiwan and China combined make up about 70% of global semiconductor production, U.S. gains in production share could put local job creation and associated domestic capex by South Korea and Taiwan at risk.

3: The potential for a Trump victory

There’s considerable uncertainty around former President Trump’s trade policy, but if he wins another term in office, it may raise the specter of a much broader approach to tariffs and export controls, the authors believe. It’s unlikely Trump would reverse Biden’s export controls on China, but he has publicly floated a 60% tariff on Chinese imports and 10% across-the-board tariffs.

A favored Trump metric in driving trade policy appears to be the U.S. trade balance, and key targets of U.S. trade-policy tensions could be China, the EU, Mexico and possibly Vietnam. China will likely be the target of the most punitive trade measures, the authors predict; after all, it’s the largest contributor to the U.S. trade deficit and its strategic revival.

But they see Trump’s proposed tariffs more as bargaining chips; 15% tariffs with some trade diversion is a more likely outcome, they say. What’s more, China’s options for retaliation are seemingly limited, beyond letting the renminbi depreciate; targeting U.S. multinational corporations in China seems improbable due to the fear that it would result in a backlash.

The EU could be a Trump target due to long-standing grievances over a digital services tax and market access. Another issue is EU trade restrictions on Chinese goods and investments and divergence from the U.S. position.

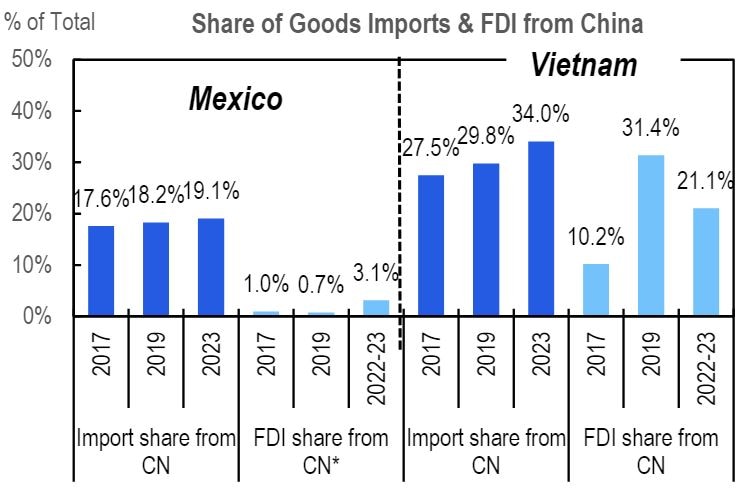

Lastly, because there is some evidence that China exports to the U.S. are being rerouted through third countries like Mexico and Vietnam -- which would undermine de-risking, let alone “strategic decoupling.” -- these countries could also attract U.S. scrutiny.

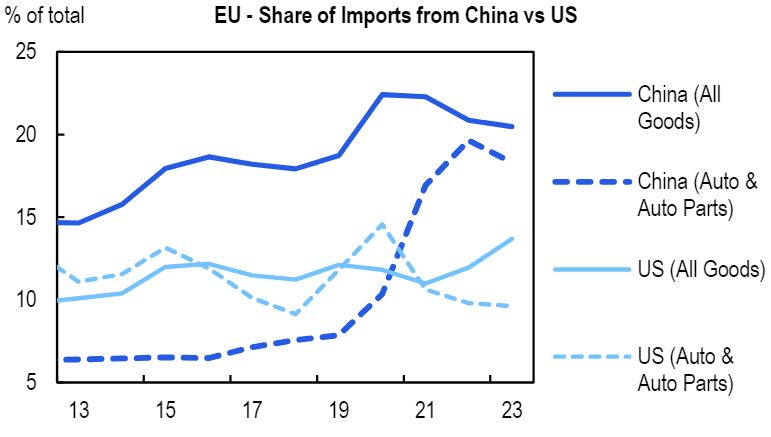

US might think EU is not doing enough to de-risk supply chains from China

© 2024 Citigroup Inc. No redistribution without Citigroup’s written permission.

Source: Eurostat, Citi Research

Share of Chinese Imports and FDI in Mexico and Vietnam have been on the rise since 2017

Source: CEIC, Citi Research.

© 2024 Citigroup Inc. No redistribution without Citigroup’s written permission.

Source: CEIC, Citi Research. Note: *WE take CN(+HK)'s sare of FDI excluding US to remove the outsized role of US FDI into Mexico.

4: The EU may harden its trade stance on China

The EU is a key battleground for geoeconomic fragmentation, the authors note. As a bloc, it’s the largest trading partner of both the U.S. (18.5% of total goods trade) and China (13%). Despite a political alliance with the Western bloc, the region has made only a marginal shift in its reliance on Chinese imports, with the share of imports rising in recent years for some key products.

According to the authors, European officials will push back on Chinese trade in coming years. China’s focus on industrial upgrades is putting industries in the EU at a disadvantage, and there’s increased recognition that China’s unbalanced growth strategy and consequent excess capacities are a much more systemic problem for the EU.

That said, the EU’s strategies to de-risk trade will be targeted and slow, the authors surmise, in part because the EU Commission lacks the executive powers of the U.S. presidency. China also needs the EU as a key market for its “strategic emerging industries” — green goods — and stands to lose economically from increased barriers.

In the authors’ view, this would jeopardize the big bet made by China’s leaders on high-tech manufacturing as a source of growth. Demand from domestic sources and the Global South will likely be insufficient to absorb China’s growing industrial capacity, which suggests there’s room for China to negotiate and appease EU concerns. One obvious concession would be to facilitate more Chinese greenfield investments in the EU, shifting production of these “strategic emerging industries” to Europe.

To read more, if you are a Velocity subscriber, please see the full report here Emerging Markets Economic Outlook & Strategy - Trade De-Risking and Possible Trump 2.0* (19 April 2024)

Citi Global Insights (CGI) is Citi’s premier non-independent thought leadership curation. It is not investment research; however, it may contain thematic content previously expressed in an Independent Research report. For the full CGI disclosure, click here.

Related Stories

Citi Institute Future of Finance Forum 2025

The Citi Institute Future of Finance Forum brings together leading voices across finance, policy, and technology to explore how innovation is reshaping the financial system. With a focus on frontier technologies such as AI, blockchain, and quantum computing, the Forum connects industry experts, regulators, and thought leaders driving the next wave of transformation.

This year’s event featured guest speakers including Hon. Caroline Pham, Acting Chairman of the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission, and offered forward-looking perspectives on the future of digital assets, financial infrastructure, and global innovation. Watch the highlights video above.

Watch the replays here