Japan’s economy is emerging from 30 years of deflation and has the rare opportunity to shift to private sector led, self-sustaining growth. We explore a roadmap of how this shift might be achieved.

A new Macro to Micro report from a team led by economist Katsuhiko Aiba looks at Japan’s opportunity to emerge from 30 years of deflation and shift to self-sustaining growth led by the private sector. The aging of Japanese society has left investors seemingly less than confident about a recovery in consumer spending and sticky 2% inflation, but we see 2024 as the first year of a virtuous cycle of prices, wages and consumption — though a key factor is whether senior citizens without sufficient savings will participate in the labor force.

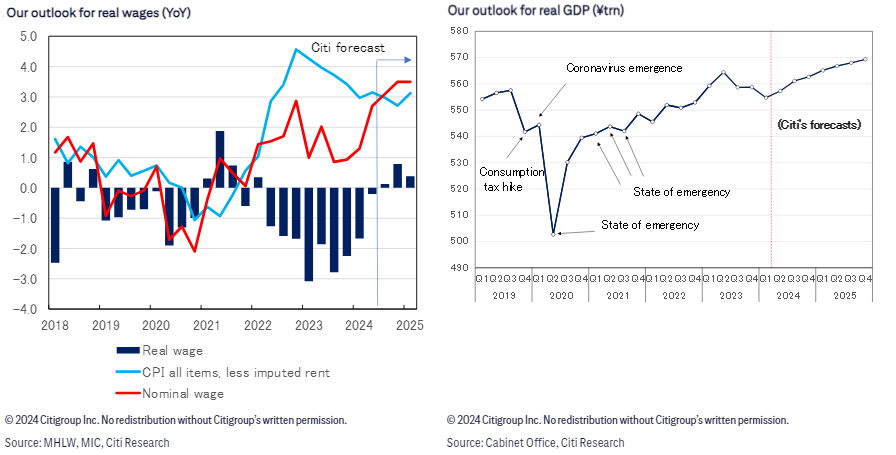

The norms for Japanese prices and wages began changing in 2022, as rising prices were fueled by the yen’s depreciation and a supply shock, combined with a labor shortage. Wage hikes agreed to in this year’s annual shuntō, or “spring wage offensive” — where thousands of Japan unions negotiate wages with employers simultaneously — are now being reflected in regular wages, and we think real wage growth will turn positive for the July–September time period. This improved income environment should translate to solid growth for Japan’s economy starting in this year’s second half, with growth driven by domestic demand centered on personal consumption.

The increases agreed to in the shuntō represent a permanent rise and so have a big impact on consumption. Real wages fell 2.2% in fiscal 2023, but we forecast that they’ll turn positive and grow 0.3% in fiscal 2024. At the same time, we think the wealth effect due to equities’ gains will support consumption, particularly among older consumers. Past research indicates that each ¥100 rise in financial assets’ value adds ¥2–¥4 to growth in personal consumption. For our purposes, we assume ¥3 and estimate the boost to personal consumption will turn positive at 0.6% this fiscal year, compared with –0.4% last fiscal year.

A note of caution, however: While the wage rise is the largest in 33 years, Japan’s population has aged during this period, meaning the sensitivity of personal consumption to real wages may have declined. Forty percent of consumers are pensioners, and few of them benefit from wage growth. Workers also pay more of their wages in social-welfare levies than they did 30 years ago. The key question is whether this year’s second-half recovery in personal consumption will help sustain inflation and make interest rates meaningful.

If this strength in personal consumption is realized, we’d expect companies to increasingly pass on personnel costs via service prices, making Japanese inflation stickier. We project core inflation of 2.5% for 2024 and 2.4% for 2025, following 2023’s 3.1% reading. We expect an increase of nearly 3% in base wages in next year’s shuntō, given higher inflation, strong corporate earnings and the labor shortage.

Should this scenario come to pass alongside a soft landing for the U.S. and other world economies, we’d expect the Bank of Japan (BoJ) to raise rates 25 basis points in December as well as in April, then look to gauge the impact of rate hikes and test the neutral interest rate — where both inflationary and deflationary pressures are absent — with hikes coming every six months. While the neutral interest rate’s level is very uncertain, at this point we put it at 1.5%, a level we expect the policy rate to reach in October 2026.

Interest rate impacts

The consensus is that interest-rate rises accompanied by an improving economy and wage growth are positive for households overall. The BoJ’s modeling, for example, finds that there’d be net growth in interest income for the 77% of households that don’t have a mortgage; for most households that are repaying a mortgage, each 1-percentage-point increase in short-term interest rates would cause a rise in the net interest burden of less than 2% of disposable income. Because we expect annual growth in nominal wages of around 3% in a regime of economic growth and changes in inflation norms, we foresee income growth after the payment of taxes and social-insurance levies, with most households able to cover the increased interest-payment burden with growth in employment income. However, some older-generation households may not be able to cope with a rise of 2% in the cost of living, meaning the safety net may need to be extended.

Corporate borrowings have grown relative to GDP since the pandemic, but much of this growth has been due to companies building cash holdings due to pandemic-related uncertainties, and a similar amount of cash and deposits has built up on the asset side of corporate balance sheets. From a long-term perspective, companies have come to depend less on borrowings, constraining capex to within the bounds of cash flow. This makes them less sensitive to interest rates; should the economy remain solid, we’d expect capex to also remain robust.

According to BoJ modeling of corporate earnings, if interest rates on borrowings rose to around 2%, operating profits would be sufficient to cover interest payments. But we note this is a static simulation; an improved economy would likely drive growth in operating profits, with corporate earnings becoming more resilient in the face of interest-rate rises. Still, the burden of interest payments could be a drag for some small companies, and it may prove necessary to extend the safety net here as well.

A roadmap for productivity improvements

Since the bursting of the Bubble Economy in the early 1990s, improving productivity has been discussed as a long-term issue for Japan’s economy. This discussion has grown in importance in recent years given the falling population and labor shortages, with the case made that an increase in inflation could boost the economy’s productivity and potential growth rate. The idea is that positive general price inflation improves the signaling functionality of wages and prices, thereby making resource allocation more efficient and having a positive effect on productivity. It’s a discussion we find interesting, while noting that at this point it’s but a theory, one that will be tested by the economy’s actual performance.

If the potential growth rate rises and real wage growth accelerates, we could see a positive cycle in prices, wages and personal consumption; once the start of such a cycle has been confirmed this year, we think the focus will shift to productivity improvements and the potential growth rate — if the external environment allows.

| How heightened inflation can raise potential growth rates, as outlined at a BoJ workshop | |

| Under a product cycle, it is desirable for the relative price of a new product to decline over time after it is introduced, but there is a price rigidity. if the inflation rate is positive, resource allocation may become more efficient as its relative price declines. | |

| Productive firms with high mark-up do not pass on costs much. Under this situation, a guarual rise in general price will encourage a shift in demand to highly productive firms, lending to more efficient resources allocation. | |

| In a market with excessive entrants, if general prices rise and costs increase, it is possible that reductions in markups will encourage companies to exit, correcting distortion in resource allocation. | |

| Wage rigidity makes it difficult to set wages according to productivity. Under higher inflation rate, ensuring flexibility in wage setting will enhance the signaling functions of wages, make resource allocation more efficient, and lead to increase productivity. | |

|

Labor-force changes?

There are doubts about whether 2% inflation can be maintained over the long term as Japan’s population ages. The optimistic view is that an ongoing labor shortage will help sustain positive wage growth and 2% inflation, but neither of those things will be sustainable if the 3% increase in wage costs that’s consistent with 2% inflation isn’t passed on in sales prices. And such pass-throughs won’t be possible if consumers’ purchasing power is too weak — a potential issue given that 40% of the Japanese population are pensioners, not workers.

As the number of people working who are pension-fund members declines, an increase in the adjustment ratio for pension benefits paid can’t be avoided. But declines in real pension benefits paid can be offset to some extent by growth in interest income. That said, we don’t expect income growth to keep pace with price rises for some households, and so expect increases in labor-force participation.

A decline in real pension income caused an increase in labor-force participation by the older cohort in the 2010s; if the pace of the expected decrease in pensions’ real value accelerates, we think we’ll see another increase in this participation. And, we note, the demand is there from firms facing labor shortages. There’s also the possibility of changes to current government policy that pension benefits are reduced for people who choose to work, or the abolition of this policy.

The 1960s saw much higher labor-force participation from Japan’s older cohort. While most older people then worked in agriculture, healthy life expectancies have lengthened and an easier work environment (such as remote work) is now taking shape. A situation in which weighting of pensions within older people’s total income decreased and the linkage to wages increased could help maintain consumers’ overall purchasing power, making it possible to sustain a 2% inflation rate.

Our new report, Roadmap for an inflationary era: Outlook for economics, yen rates, equity strategy, and financials, also includes discussion of Japan’s outlook from the point of view of yen rates, equity strategy, and financials. It’s available in full to existing Citi Research clients here.