COVID-19 has dominated our personal and business lives and remained the main driver of economic trends and financial markets during 2020; FX markets have been no exception.

Recent weeks have been characterized by sharply rising infection rates in both countries that had been unable to control the first wave of the virus and those facing second waves as earlier containment measures had been eased. The result has been varied, with most countries trying to find a more nuanced response than simply a return to the earlier lockdowns, whether in the form of curfews, particularly for high risk groups, or restrictions on the size of gatherings, thereby impacting schools and places of worship. The sharp contraction of economic activity in the second quarter was tied directly to the earlier application of such measures. It would therefore be naive to expect that new restrictions can be adopted without a negative economic impact and a pass-through to respective exchange rates.

For emerging market (EM) currencies, the progression of the pandemic – including the possibility of further waves – and the timing of the rollout of an effective vaccine will be important issues for their currency outlook in the months to come.

A “sudden stop” to capital inflows

The ability of emerging market countries to manage COVID-19 is only part of the story when it comes to exchange rates. The relative dependence of each country on foreign capital inflows – regardless of whether they are an emerging or developed market – is also important.

The sharp depreciation of numerous currencies in March and earlyApril as the pandemic escalated was predicated in large part on a “sudden stop” to capital inflows, as foreign investors became more nervous about economic prospects in target countries.i In simple terms, countries that relied on capital inflows to help balance their international accounts suddenly found that inflows had stopped. The immediate result was that either their currency depreciated sharply or they were forced to fill the gap through the depletion of foreign exchange reserves.

Economic performance and prospects have become even more negative since March as the global economy suffered the sharpest – but possibly the shortest – contraction in activity since the Second World War. Most economies have started to rebound, with some already returning to their previous trends (most notably China), but the possibility of new containment measures due to the latest resurgence of the coronavirus suggests that the outlook is far from secure. Even under a relatively positive view of the rollout of vaccines, many may find that it takes two years or more to return to previous levels of activity. All countries will face permanent costs from the slump, including widespread bankruptcies, a loss of human capital, and a decline in medium-term productivity growth. With most companies facing at best a decline in profitability and in many cases large losses, a medium-term reduction in foreign direct investment in emerging markets seems inevitable.

The standard policy response by most countries in the face of the pandemic has been to enact major cuts in official interest rates together with the adoption of large-scale fiscal support measures.ii But the cut in interest rates in particular has reduced the attractiveness of many emerging markets to fund managers. Previously, high interest rates were a buffer against other problems in a country. Now, rates are often as low as in developed economies in nominal terms and negative once risk premiums are subtracted. In other words, the buffer that once made emerging markets attractive to portfolio managers may no longer exist. This will further reduce capital inflows. While the interest rate cutting cycle may now be at an end in numerous countries (such as in Brazil and Russia), there is little prospect for rate increases in the foreseeable future.

Will IMF and MFI support remain unconditional?

The length of the pandemic will have significant consequences for EM countries. Early in 2020, the prevailing view was that it would be past its peak by the middle of the year. While that may be the case in China, it is certainly not in the majority of the global economy. One lesson from the pandemic is that even if one country has eliminated the virus, it cannot relax restrictions unduly given the risk from the rest of the world. The prolonged nature of the pandemic means that investments that may have been merely delayed early in the year could now be canceled. Countries that had presumed that the halt to capital inflows would be temporary are now recognizing that it could be prolonged.

There have been fewer EM exchange-rate crises this year than might have been anticipated. Some countries with good credit ratings have been able to offset the loss of capital inflows by issuing debt in international markets. Poorer countries have been able to access emergency funding from the IMF and other multilateral financial institutions (MFIs) without any insistence on policy reform, i.e. without conditionality. So far 81 countries have received financing from the IMF, while 28 have benefited from debt service relief. iii

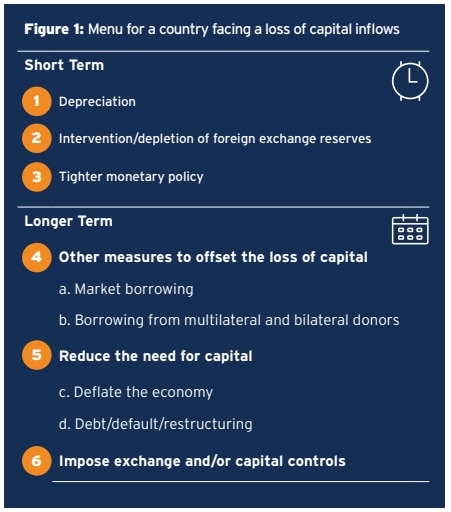

However, as the crisis becomes more protracted, there will be questions over whether MFIs are willing to continue lending without the application of conditionality, and whether countries will be willing to accept conditionality and increased debt levels. Instead, the obvious concern is that countries could resort to less marketfriendly remedies (see figure 1).

Foreign capital flows will be critical for many currencies

The traditional breakdown of countries into developed economies and emerging or frontier markets has been increasingly questioned in recent years. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has rendered these distinctions largely irrelevant in formulating a currency outlook. Instead, the crucial issues have become a country’s dependence on foreign capital inflows and its relative creditworthiness. Until the global economy returns to normal, or at least until capital flows resume at a more regular level, this distinction will remain critical to the exchange rate outlook.

The first use of the term is associated with the Rudiger Dornbusch and Alejandro Werner, who noted that “it is not speed that kills, it is the sudden stop” in “Mexico: Stabilization, Reform and No Growth”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1:1994. It is noteworthy that this was published well before the onset of the Mexican crisis that erupted in December 1994, which triggered a dramatic depreciation of the Mexican peso.

ii Mexico is the notable exception. Under President Lopez Obrador, the focus has been on a continuation of fiscal austerity, while the central bank has been more cautious than most in cutting interest rates.

iiiSee imf.org/en/topics/imf-and-covid19/covid-lending-tracker.