One of the most dramatic societal shifts of the 21st century will be the demographic transition to a population that is older than it ever has been.

In the nineteenth century, no continent had a life expectancy of more than 40 years. By 2019, the average person could expect to live to 73 years old. Driven by declining childhood mortality and improved access to high-quality healthcare, these gains in life expectancy are an extraordinary achievement of global development.

Declining fertility compounds population aging, and it is driven by efforts in global development too. Rising rates of education and increased access to contraception have pushed down the number of children that families have.

Yet population aging has far-reaching consequences that governments, businesses, and wider society must reckon with. Economists have already sounded the alarm bells on some of these consequences: a ballooning older population will be dependent, they say, on a working-age population that is too small to support it.

We argue that, while the trend towards a population that is older than it ever has been is intractable, the trend towards an increasingly dependent one need not be.

In this report, we collate perspectives from across Citi and our global network to explore how our extra years of life expectancy can be lived as social contributors rather than dependents. From these expert contributions, we find that supporting the health and wealth of an aging population are the levers to pull if our aim is to minimize the dependence of an aging population. We see four dimensions:

- Maximizing the economic contribution of older groups, including evolving labor markets in support of longer working lives.

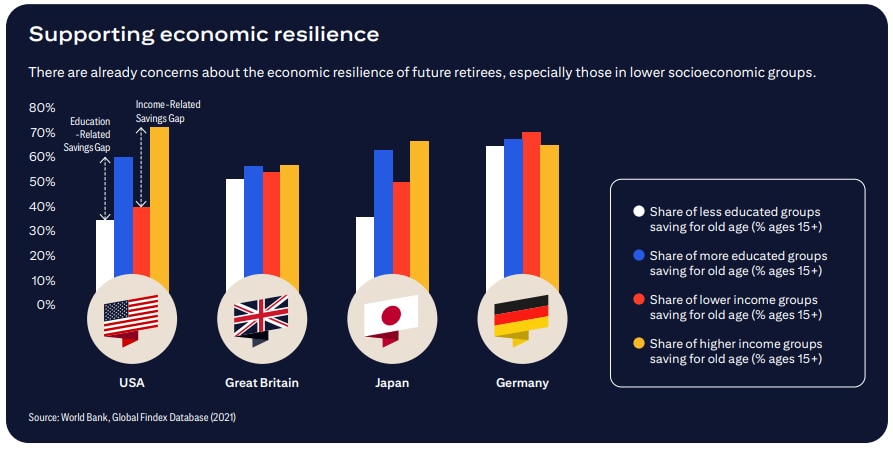

- Supporting economic resilience in later life, through financial inclusion and incorporating longevity into financial planning.

- Preventing the onset of dependence by supporting healthy aging, including the shift to a more preventive healthcare system.

- Ensuring access to affordable healthcare for all, including boosting the supply of care work and joining up health and care systems.

This demographic transition is not happening in a vacuum: some wider shifts already abate the potential economic consequences of population aging. For example, technologies like artificial intelligence which could prop up the productivity of a shrinking workforce are already being adopted.

Other elements of the response require more action – like joining up health and social care or increasing labor market flexibility. We therefore conclude the report with concrete recommendations for businesses to respond to the demographic transition, which we have co-produced with the Global Coalition on Aging.

We hope this report helps to shift the discussion of population aging towards an optimistic vision in which we can spend our extra years as healthy and active participants in flourishing, and merely numerically older, societies. After all, what good are longer lives if we cannot truly live them?